Uganda is entering a critical political period. As the country prepares for the 2025/2026 general elections, debates about leadership, fairness, legitimacy, and youth representation are intensifying. At the center of this storm are several key figures: Elizabeth Kakwanzi Katanywa, a youthful aspirant for Western Youth MP; President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, seeking another term; Norbert Mao, newly handed leadership of IPOD; and a broader wave of youth participation and concern about how elections will be conducted. What follows is a detailed narrative of what’s at stake, what’s happening now, and what the future may hold.

Elizabeth Kakwanzi Katanywa: A Voice of Youth, Under Pressure

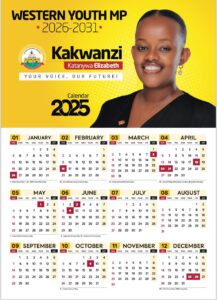

Elizabeth Kakwanzi Katanywa is running for the Western Youth Member of Parliament (Youth MP) seat in Uganda, under the National Resistance Movement (NRM). Her campaign began in earnest around August 2024, and since then she has made multiple public appearances, videos, and statements, engaging supporters across Western Uganda.

In a video which she released as an official statement (leaked, but confirmed by her campaign), Kakwanzi detailed a range of challenges she’s faced: intimidation, blackmail, voter bribery, and cyberbullying.

These are not just political complaints—they represent real barriers to fair competition and democratic participation. Despite this, she has emphasized resilience, dignity, and unity among her supporters, urging calm, commitment, and a shared vision for a better future.

One immediate effect of some of the issues she raises is tied to scheduling: the Electoral Commission has adjusted nomination dates for Local Government Councils and Special Interest Groups elections—which include youth representation—causing uncertainty about when elections will be held. Kakwanzi’s message is that although the originally scheduled voting dates have been disrupted or delayed, supporters should remain calm and focused, because a new date will be set.

Her campaign comes at a moment of broader national urgency: many young Ugandans are not just looking for political representation, but for meaningful economic opportunities. Agriculture, sustainable livelihoods, climate action, and youth empowerment are major issues among her platform and among youth more broadly

Museveni, the Presidency & Power Dynamics

President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, having ruled Uganda since 1986, has confirmed his intention to run again in the 2026 general elections.

At 80 years old, Museveni remains a central and highly polarizing figure. His leadership is credited by supporters with stability, infrastructure development, and some economic growth; critics counter that his nearly four decades in power have seen weakening democratic institutions, increasing constraints on opposition, and allegations of misuse of state resources to suppress dissent.

One significant recent development is Museveni’s handover of the Chairmanship of the Inter-Party Organisation for Dialogue (IPOD) to Norbert Mao, leader of the Democratic Party. This happened at the recent IPOD Summit on September 18, 2025, held at the Kololo Ceremonial Grounds in Kampala

IPOD & Norbert Mao: What’s Changing

IPOD is designed to be a platform for political parties in Uganda to dialogue, build consensus, and help ensure peaceful and inclusive democratic processes. Under Museveni’s leadership, IPOD has functioned, in theory, as a space for negotiation and oversight, though critics often say it has had limited teeth when the real political pressures come

The transition of IPOD’s chairmanship to Hon. Norbert Mao (DP) is symbolically significant. It suggests a gesture from President Museveni toward shared leadership in dialogue with opposition parties and more inclusion of other party actors in political processes

Mao, already Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, has stated publicly that under his leadership IPOD should emphasize consensus, peaceful engagement, and free and fair elections.

Nevertheless, not all opposition parties are uniformly supportive of this shift. At least some see danger in “backdoor” consensus, worrying that important decisions may be made behind closed doors among a few political elites, rather than through transparent, democratic means. For example, Mao has been quoted suggesting that a “consensus bloc” is already in formation—one that includes parties such as DP, UPC, and others—that may work together both within and outside formal electoral processes.

The Tension between Process & Legitimacy

A recurring theme in all of this is the tension between having processes that look democratic (election dates, nomination windows, multi-party platforms) and having substance and legitimacy (free competition, no coercion, no intimidation, trustworthy outcomes). Kakwanzi’s campaign has drawn attention precisely because she alleges many of the negative factors: blackmail, voter bribery, cyberbullying, and the postponement or alteration of election schedules. These are serious because they chip away at the confidence people have in the process.

Meanwhile, the IPOD change hints at attempts to manage political conflict through dialogue, inclusion, and institutional handovers. Yet, for many Ugandans—especially youth—seeing a power transition in practice (i.e. someone other than Museveni in the presidency via credible election) matters more than symbolic changes or consensus among political elites. The question is: will the changes underway produce an environment where someone like Kakwanzi can compete fairly, free from coercion and obstruction?

Youth & Representation: What’s at Stake

Youth in Uganda are a large and growing proportion of the population. For many of them, frustrations include unemployment, lack of access to land or capital, limited political influence, and in some regions, under-representation. The Youth MP positions—for the Western region and others—are among the few formal institutional channels through which young people can have representation in decision making. Kakwanzi’s campaign, and others like hers, are not only about seats but about symbolic and practical inclusion: being heard, being allowed to influence policy, being able to push for economic and social change.

Often, these youth candidates face obstacles. Beyond the regular hurdles of campaigning (travel, finances, networks), they must also navigate political intimidation, allegations of vote-buying, cyberbullying, and sometimes direct suppression. Kakwanzi’s account is a case in point: her campaign has received both local support and resistance.

Power Transfer, or Continuation? The Debate Over Leadership Change

One of the most talked-about issues in Ugandan political discourse in recent days is whether the upcoming elections will represent a genuine change in leadership or simply another reaffirmation of Museveni’s rule. On one hand, Museveni has formally announced his intention to run. On the other, there are signals—such as the handing over of IPOD’s chairmanship—and statements by some politicians that a transition (whether through elections or consensus) is underway.

Norbert Mao has made comments suggesting that a transition may not only be electoral, but also relational—meaning agreements, negotiation, consensus among political actors may shape the way power evolves.

Some opposition figures criticize this, arguing that any “transition” must happen openly and legitimately, not behind closed doors or via informal arrangements that exclude those with opposing views.

The presence of Museveni’s family members in political discussion (for instance, his son, Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba) also complicates the picture—both in how power might be transferred, and in regards to public perception. Some see that involvement as a sign of grooming or succession planning, others see it as further extension of the existing power structure.

IPOD Summit & Dialogue: Hope or Delayed Change?

The recent IPOD Summit—held under the theme “Together for a Peaceful and Sustainable Uganda”—was marked by both hopeful gestures and pointed warnings. President Museveni handed over the IPOD chair to Norbert Mao, urging political actors to adopt peaceful engagement

Mao in taking over has committed publicly to ensuring free, fair, and peaceful elections in 2026. He has also emphasized consensus building and dialogue among parties.

However, many challenge whether dialogue alone is enough. Delays in election schedules, adjusted nomination dates, unaddressed allegations of abuse, and concerns about political space remain central concerns for civic actors, youth groups, and opposition parties. Institutional reform (like credible electoral commission performance, judicial independence, media freedom) are seen as essential alongside any leadership or dialogue transitions.

What Elizabeth Kakwanzi’s Case Tells Us

Kakwanzi embodies many of the trends and tensions in Uganda’s politics today:

- Youth ambition: She represents young people seeking not just representation but voice and agency.

- Challenges of fairness: Her reported experiences of intimidation, bribery pressures, and online abuse are not isolated. They reflect broader systemic issues many candidates (especially young, opposition or less established ones) face.

- Delayed or shifting electoral processes: Postponed or altered nomination dates raise questions about whether electoral frameworks are being manipulated, or are simply inefficient.

- Resilience & public support: Her public messaging emphasizes hope, dignity, unity—indications that despite challenges there is broad community backing and belief in democratic possibility.

What to Watch For in the Coming Months

Based on current developments, here are key indicators that could show whether change toward more open and fair political competition is happening—or whether the status quo will prevail:

- Timely, transparent election and nomination schedules

If nomination and voter registration dates happen as announced, without arbitrary delays, that’s a positive sign. - Security and fairness during campaigns

Monitoring how security forces interact with candidates like Kakwanzi; whether there are reports of intimidation, violence, or suppression; how electoral laws are enforced. - Media space and freedom of expression

Whether voices critical of the government, or less powerful candidates, are allowed to campaign freely, to speak in public, on social media, in debates, without fear. - Functioning IPOD & opposition participation

Under Mao’s leadership, whether IPOD acts as a real forum for oversight and meaningful dialogue, or whether it becomes symbolic. - Public perception & youth engagement

How youth view participation: if watches, rallies, community organising, petitions etc. are allowed; and whether youth feel represented and heard. - External observers & civil society monitoring

How local and international organisations perform election observation; whether they find credible complaints; whether their findings are respected or suppressed.

Elizabeth Kakwanzi Katanywa’s campaign is more than a run for a seat—it’s a litmus test for Uganda’s democratic health. Her experience of blackmail, cyberbullying, and alleged manipulation does not stand alone; it is part of a broader narrative in which the process of elections is as important as the outcome.

At the same time, there are hopeful signs: IPOD’s leadership handover, calls for peaceful dialogue, broader youth interest in political and economic change, and candidates who refuse to be silenced. The upcoming elections will tell whether these signs turn into real shifts.

For Kakwanzi and her supporters, for young Ugandans, and for all Ugandans invested in democracy, the stakes are high. Will the 2026 elections be another reaffirmation of known power structures—or the moment when competing voices overcome barriers and offer alternatives? The world is watching, and the answer may rest on how fairly the process is conducted, not just who wins at the ballot box.